Ivolginskii datsan Gandan Dashi Choinkhorlin, the Republic of Buryatia

By Ekaterina Sobkovyak

Ivolginskii datsan (Tib. grwa tshang) Gandan Dashi Choinkhorlin (Tib. dga’ ldan bkra shis chos ’khor gling) is a Buddhist monastery situated in the territory of the Republic of Buryatia (Russian Federation), about 25 km west of the centre of Ulan-Ude, in the village of Verkhnyaya Ivolga. This monastery is presently the centre of the Buddhist Traditional Sangha of Russia (hereafter, BTSR), a centralised religious organisation and the largest Buddhist community of Buryatia. As the residence of its head, the Pandito Khambo Lama, it occupies a special place in the history of Buryat Buddhism. It continues a tradition that began in the middle of the 18th century when the Buryats built their first stationary Buddhist monasteries, representing a new, peculiar turn in its development.

The extraordinary history of Ivolginskii datsan formed the unique nature of its material dimension. The entirety of material items accumulated, preserved and utilised within a complex of architectural structures which mark all together the place known as Ivolginskii datsan, has, in its turn, influenced considerably the course and dynamics of development of the Buryat Buddhist tradition and Buddhism in Russia.

Accumulation begins: The foundation of the monastery

Ivolginskii datsan came into being under extraordinary circumstances. After the October Revolution of 1917 and the overthrow of the Russian monarchy, the religious policy that the new communist power implemented led, by 1941, to no active Buddhist monasteries existing in Transbaikalia. The antireligious campaign and political purges of the 1930s saw hundreds of Buryat Buddhist monks defrocked, arrested, sent to prisons and concentration camps and executed. The property of all the demolished Buddhist monasteries and temples was partially destroyed, partially sent to museums and academic institutions (Zhukovskaya 2001: 26-27).

Scholars still disagree about the reasons the USSR government allowed in 1944 a Buddhist monastery in Buryatia (at that time, Buryat-Mongolian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic; hereafter, BMASSR) to reopen. Some consider this to have been a political move aimed at proving the existence of the constitutionally proclaimed freedom of conscience and practice of any faith (Ibid.: 27). Others presume that it was a gesture of loyalty and gratitude to the Buryat Buddhists who conducted patriotic activities and collected a significant sum of money for the Defence Fund during World War II (Chimitdorzhin 2019: 206). Still others believe that the Soviet government chose to deal with the active revitalisation of religious life among the Buryat Buddhists by opening one officially registered Buddhist association under full state control (Batomunkueva 2023: 67-68). Be that as it may, on May 3, 1945, the Council of the People’s Commissars of the BMASSR issued a decree allowing a Buddhist temple, ‘Khambinskoe sume’, in the settlement of Srednyaya Ivolga, to open and register 10–15 monks to serve in it. Further, the Council for the Affairs of Religious Cults and the Council of the Peoples Commissars of the USSR approved this decree (Ibid.: 69).

Initially, the mounting of the temple buildings occurred in the area called ‘Tokhoy-Shibir’ (according to alternative sources, ‘Oshor-bulag’ (Chimitdorzhin 2019: 221)), but in 1947, they were moved to the more elevated place called ‘Mangazhin-dobo’, which has remained the monastery’s location until now (Batomunkueva 2023: 70). According to the official decree, the temple should have opened in a former praying house ‘Mani’. Conventional history says that additions to the original building included an extension in 1947, and the second floor and the balcony in 1948. The gold-plated ganzhir (Tib. gan ji ra; Skt. gañja) and the ‘Wheel of the teaching’ (Tib. chos kyi ’khor lo; Skt. dharmacakra), together with the statues of two deer, that Khambo Lama Darmaev brought from the region of Zakamna, completed the external appearance of the temple. The datsan then officially received the name ‘Dashi Choinkhorlin’ (Chimitdorzhin 2019: 221). According to some archival sources, however, the newly established Buddhist monastic community received two buildings as donations from the local women devotees. Put together, these houses formed the building of the monastery’s first main assembly hall, Sogchen dugan (Tib. tshogs chen ’du khang) (Batomunkueva 2023: 70-71). In fact, in its initial stage, all the things that the monastery required came ‘second-hand’, entirely from the local Buddhist laity and former monks.

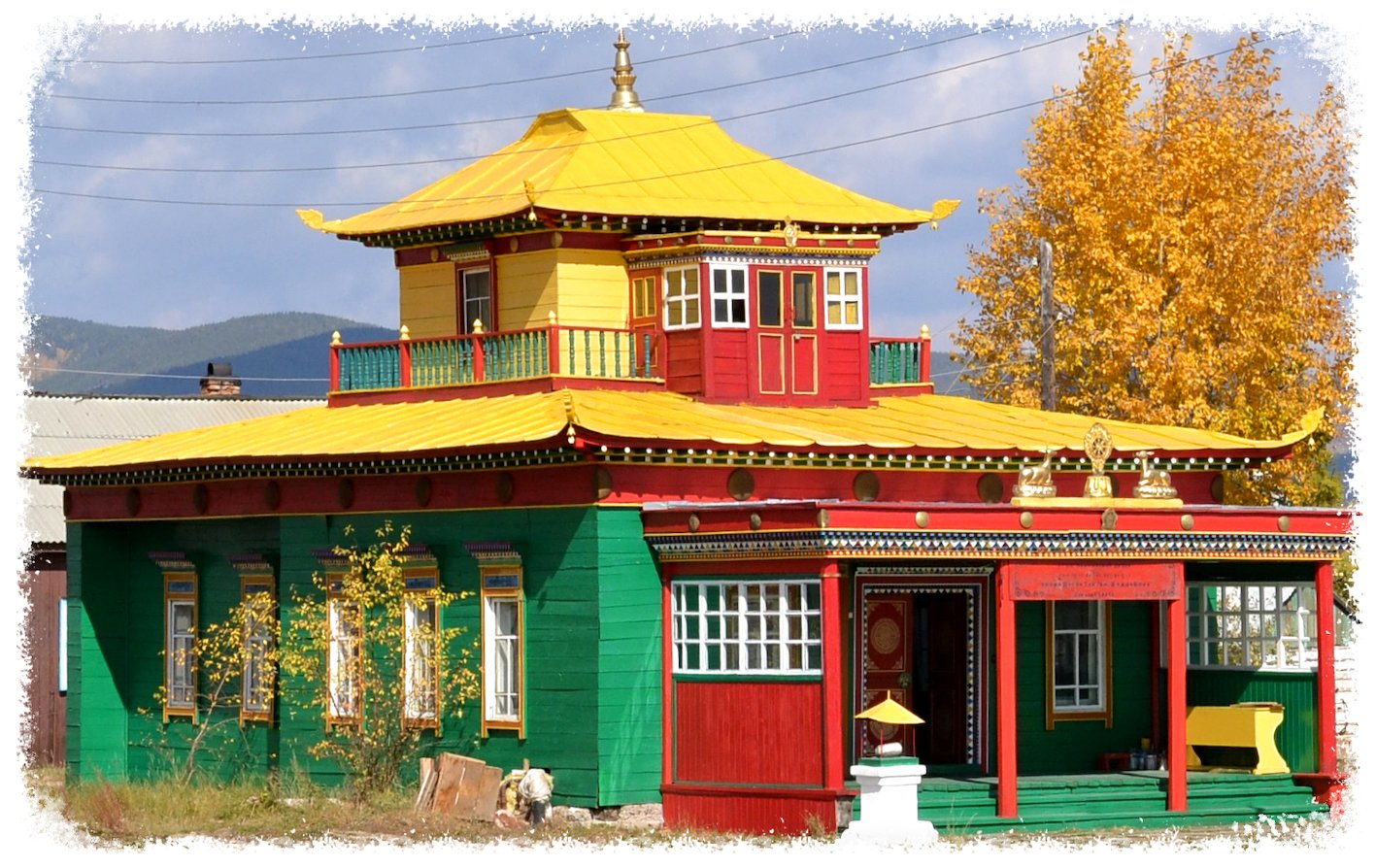

Figure 1. The first Sogchen dugan. Currently – Choira dugan. September 2014 [1].

Since the late 17th century, when the building of Buddhist monasteries on a large scale began in the territories that the Mongolian peoples inhabited, a broad and dense network of political, cultural, commercial and private connections appeared to provide these religious institutions with the things indispensable for their spiritual and secular activities. Initially, the Buryats imported religious literature from different regions of the Qing empire, including Tibet, Beijing, Dolon Nor and Ikh Khuree. Ritual paraphernalia and cult utensils, thangkas, statuary and religious goods for the lay market also arrived from Inner and Outer Mongolia, and Beijing. However, by the second half of the 19th century most of the Buryat Buddhist monasteries already had their own printing houses that issued numerous volumes in Tibetan and Mongolian and, to a large extent, met clergy and laity needs for Buddhist literature. Several centres of arts and crafts also appeared, in which both lay and monastic artisans produced wooden, metal, clay and papier-mâché Buddhist statuary, items of inner and outer décor for the places of worship, furniture and other religious ceremonial and utilitarian equipment. By that time, the Buryat thangka-painting tradition had reached its heyday, with many local artists creating their works in an original manner that differed from the Tibetan, Mongolian or Chinese styles (Charleux 2010: 78-90; Syrtypova et al. 2006: 51-73; Zalkind 1972: 286-88, 412-14).

When Ivolginskii datsan opened, most of the centres of production and distribution of Buddhist religious artefacts, as well as the former trade routes and logistic infrastructure, were gone with the Qing and Russian empires. Nevertheless, the Buryats managed to provide their newly opened datsan with all the things essential to making it look like and function as a Buddhist monastery. Its architectural complex and assemblage of tangible assets grew continuously in the following years, with various augmentations.

The formation of the collection: Monastery development during the Soviet epoch

Since its foundation, despite the continuous strict antireligious policy that the Soviet state enforced, Ivolginskii datsan developed steadily, at least as regards its material base. Already in 1951, an additional plot of allotted land extended the monastic complex, the major construction works for which occurred in the 1970s. A new Sogchen dugan rose in 1970–1972, as a wooden three-storey construction on a stone basement. When fire destroyed it in February 1976, it was rebuilt within six months and reopened in November of the same year. A small wooden temple of Maidari (Tib. byams pa; Skt. maitreya) sume (1970–1973) and a mud-walled building of Devazhin (Tib. bde ba can; Skt. sukhāvatī) sume (1970) were erected. By the end of the 1970s, the complex also included a two-storey guesthouse, the bureau of the Central Spiritual Administration of Buddhists (hereafter CSAB) of the USSR and four suburgans (Tib. mchod rten; Skt. stūpa) (Chimitdorzhin 2019: 222).

Figure 2. Sogchen dugan built in 1976. August 2011.

At that time, the monastery expanded its collection of tangible objects mainly in three ways: (1) donations and gifts from the Buddhist laity; (2) return of religious artefacts from the state museums and libraries; (3) presents from foreign and international Buddhist organisations and monasteries, politicians and public leaders.

Figure 3. Devazhin sume. August 2011.

The first of these might have been the most important, but it is simultaneously the least well-documented. The financing of all the monastery buildings erected in Soviet times came from the money the local lay Buddhist community collected. People worked for free in the construction activities. Many donated building materials, food, household items, Buddhist ritual objects (Batomunkueva 2023: 70) and sacred books, which they had hidden from the local communist authorities in the 1930s (Chimitdorzhin 2019: 221). The names of those numerous donors and the exact information on their contributions were unregistered and remain predominantly unknown.

More data exist on the instances of artefacts that secular cultural and academic institutions returned to the Buddhist monastery. In 1934, the Antireligious Museum was created in Ulan-Ude. One of its main purposes was to find, study and preserve religious (including Buddhist) artefacts of high cultural value. The museum employees made many field trips to closed, demolished and plundered monasteries and fetched numerous articles to the museum. Sometimes, the Buddhist monks themselves asked the museum to take care of sacred objects, seeking to prevent their loss. By 1940, the museum collection numbered over 10,000 pieces (Balzhurova 2014: 112-13).

In 1957 and through the 1990s, the museum passed to Ivolginskii datsan for gratuitous use several thousand items, including 132 volumes of the Buddhist canonical collection, Kanjur (Tib. bka’ ’gyur), in Tibetan and written on black lacquered paper with nine precious substances (Bazarov 2014: 122-25) [2], or the unique wooden statues of Buddhist deities that the famous Buryat artist Sanzhi-Tsybik Tsybikov and representatives of his school created.

Thus, many religious artefacts that now comprise the material basis of Ivolginskii datsan were repurposed at a certain stage of their cultural biography. As Morgan puts it, their classification shifted from sacred, devotional objects to collectibles, antiques and cultural pieces of artistic or historical value (Morgan 2017: 27). However, they eventually reverted to their original functionality, moved from the museum and library storage back to the authentic cultural environment, for utilisation as originally intended, namely, within the walls of the active Buddhist monastery.

Figure 4. Suburgans. August 2011.

Another way that Ivolginskii datsan added material objects to its collection was through the activities of the CSAB of the USSR, the main governing body of all Soviet Buddhists, which had resided in the monastery since 1946. The state authorities allowed the Administration to establish diplomatic relations with foreign international Buddhist organisations and conduct international activities, under the strict control of the special services. The Administration energetically undertook this mission. It became a participant in the World Fellowship of Buddhists (hereafter, WFB) in 1956, and in 1970, in the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace (hereafter, ABCP). Taking part in the WFB and ABCP conferences, the Administration’s members made numerous trips to such venues as India, Thailand, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Japan, Laos and Mongolia. The Administration also hosted numerous foreign delegations, such as those from Cambodia, Japan, Ceylon, Sikkim and Burma. The Dalai Lama first visited Buryatia in 1979, and again in 1982 and 1986 (Chimitdorzhin 2019: 254-65).

An integral part of all such meetings and activities was a gift exchange. Among the items that foreign religious leaders, politicians and high-ranking clerics presented to the monastery were such devotional objects and paraphernalia as deity statues, tangkas or sacred texts, as well as memorabilia of different occasions and meetings. For example, in 1972, Mongolian Khambo Lama presented to the monastery a statue of the Buddha Maitreya and two Bodhisattvas. The Maidari sume was later built specially to house these images (Ibid.: 222).

The phenomenon of Itigelov: A transcendent miracle that makes a real difference

The beginning of the democratic changes in the Soviet Union in 1985 and its subsequent collapse in 1991 significantly influenced the life of Ivolginskii datsan. On the one hand, Buddhist clergy managed to maintain the steady growth of the monastery’s material basis. In 1986, a new Sakhyusan dugan—a wooden temple devoted to the deities-protectors of the Buddhist teaching Lhamo (Tib. lha mo) and Zhamsaran (Tib. lcam sring)—was built, and the opening of the Zhud (Tib. rgyud; Skt. tantra) dugan in 2001, the Maani dugan (a temple of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara) in 2005, the Gunrig (Tib. kun rigs) dugan (devoted to the Buddha Vairocana) in 2013 followed (Ibid.: 223) [3]. In 2010, after 5 years of construction works, an impressive temple of the Green Tara was finished.

Figure 5. Green Tara dugan. August 2011.

On the other hand, the sociopolitical and religious status of the monastery might have begun to decline, due to it having lost its exceptionality. Already in 1991, eight restored Buddhist monasteries were consecrated in Buryatia, with many others to open in the following years. The country officially registered many new Buddhist communities and organisations. Many have not accepted the supremacy of the BTSR, into which the CSAB converted in 1997 (Ibid.: 273-75; Holland 2014).

Figure 6. Maani dugan. August 2011.

Under such circumstances, the importance of Ivolginskii datsan acquiring its most precious relic—the imperishable body of the Khambo Lama Dashi-Dorzho Itigelov [4]—is difficult to overestimate. The relic itself is the well-preserved body of Itigelov, who, in 1927 at the age of seventy-five, entered deep meditation and ‘left’ the corporeal plane of existence. When the body was exhumed on September 10, 2002, it was still in the lotus meditative pose, with soft muscles, elastic skin, movable joints and no major signs of decay. Transported to Ivolginskii datsan, it was placed in a glass cube and put in the upper part of the Sogchen dugan (Ershova 2018: 1162-64). Since 2008, the body has resided in a specially built Pandito Khambo Lama Itigelov Palace. Eight times per year, during big Buddhist celebrations, the body is available for ‘common worshipping’, when everybody can come and pay homage to the sacred remains. The relic has its custodian, who acts also as an oracle, regularly receiving short messages from Itigelov.

The possession of the imperishable body immensely raised the datsan’s status, making the monastery world-famous and attracting numerous tourists and worshippers. It gave impetus to the creation of the Khambo Lama Itigelov Institute [5], which studied the Itigelov phenomenon, convened international conferences, published books and shot films on the topic. The accounts of Itigelov created in social media provide direct communication between the lama and the believers, publishing his messages daily by passing them through the oracle, with comments by the Khambo Lama Ayusheev [6]. Itigelov became the key figure of the digital world the BTSR created to promote its worldview and Buddhist teaching and to attract more followers. This quickly charismatised the personality of Itigelov, and a cult developed around it. The Khambo Lama Ayusheev widely uses the very high-level religious and cultural status of this relic, applying the opening/limiting of access to Itigelov’s body as an instrument for constructing relations with politicians, state authorities, public figures, celebrities and businessmen (Badmatsyrenov et al. 2018: 307-308, 312-14).

Figure 7. Pandito Khambo Lama Itigelov Palace. August 2011.

Turning accumulation into a museum collection

The opening of the Museum of the History of Ivolginskii datsan on September 17, 2019, was a significant moment in the monastery’s history, which marked a shift from ‘accumulation’ to ‘collection. The administration of the monastery and the National Museum of the Republic of Buryatia initiated the organisation of the museum as a sociocultural project that won a Russian ‘President’s Grant’ (thus, the State financed the whole project). The peculiarity of the project was the close cooperation between monastic and academic specialists. The abbot of the monastery supervised the project, coordinating the work of several employees of the National Museum, the Institute of Mongolian, Buddhist and Tibetan Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Federal service for monitoring compliance with cultural heritage protection law, the vice-rector of the monastery’s Buddhist University Dugdanov, the University teacher of Buddhist painting Dorzhiev and others. The scholars studied about 600 objects from the monastery collection and prepared detailed descriptions that included reference information and photos. A specially erected building houses the exposition of around 300 articles. To meet museum standards, exhibited items underwent the necessary restoration/conservation work. The artefacts not yet included in the exposition were systematised, packed, marked and stored in museum lockers.

The declared goal of the museum establishment is multifaceted. It is officially formulated as the preservation of the unique cultural heritage of Russian Buddhism, the fixation and systematisation of this heritage kept in the monastery, the actualisation and popularisation of the role that the monastery has played in preserving the Buryat Buddhist cultural and historical memory since 1945 [7]. The museum is positioned not only as a cultural-educational institution but also as a tourism object that will enhance the formation of society’s ethnocultural, spiritual, ethical and tolerant foundations (Balzhurova/Boronoeva 2020: 130-31).

A never-ending story

The re-evaluation of some parts of the monastery’s collection into historical evidence and pieces of art that accompanied the museum’s opening apparently has not reduced the datsan’s accumulative potential.

Symbolic presents, such as a statue of the Buddha Shakyamuni (which the XIV Dalai Lama presented in 2019) [8], a new edition of the Kanjur in Classical Mongolian [9] or a bronze statue of Bakula Rinpoche [10] (both of which the Indian government gifted to the monastery in 2022) back up the monastery’s intensive international relations.

In June 2020, the monastery received and consecrated a new jade statue of the Green Tara ordered in the Art Studio of Natal’ya Bakut (Irkutsk).

The donations of around twenty commercial, energy and mining companies are supporting a new building of the Sogchen dugan, currently under construction [11]. The datsan’s own creative workshop, Erkhim Darkhan, produced many pieces of the inner and outer décor for the dugan, including a thousand bronze sculptures of the Buddha Shakyamuni for the altar [12].

Morgan remarked that ‘culture is conservative in its tendency to reproduce’. Tangible objects are instances of a material culture that precedes them and is renewed and extended by them. For the culture to last, the objects are reproduced incessantly, which also leads to their endless circulation (Morgan 2017: 15, 27). Supporting this theory, the material part of Ivolginskii datsan is, indeed, being reproduced, renewed, and extended uninterruptedly.

Figure 8. Sogchen dugan. October 2023.

Figure 9. Sogchen dugan. October 2023.

Figure 10. Sogchen dugan. October 2023.

Notes

[1] All the pictures of the datsan’s exterior in this essay are from the author’s private family archive. The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to Nikolai Tsyrempilov who took the pictures of the Sogchen dugan interior (Figures 8, 9 and 10) on her request specially for this publication.

[2] This Kanjur belonged initially to the Tsugol’skii datsan and was returned there in 1996.

[3] https://ulanudefreetour.ru/дуганы-иволгинского-дацана/

[4]Other name variants are Itigilov, Etigelov. He was an abbot of the Yangazhinskii datsan (1904–1911), a recognised incarnation of the first Buryat Pandito Khambo Lama Damba-Darzha Zayaev (1711–1776), the 12th Pandito Khambo Lama (1911–1917).

[5] In 2021, the duties of the Institute were transferred to the newly established Fund of the Khambo Lama Itigelov’s legacy.

[8] https://ivolgdatsan.ru/news/137/

[9] https://ivolgdatsan.ru/news/349/

[10] https://ivolgdatsan.ru/news/352/

Bibliography

Badmatsyrenov T.B., Skvortsov M.V., Khandarov F.V. (2018)‘Buddhist digital practices of transcendence: VK-community “Hambo Lama Dashi-Dorzho Itigilov”’, Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 2 , 301-324.

Balzhurova, A.Zh. (2014) Buryatskaya Buddiiskaya Ikonopis’ kontsa XVIII-pervoi chetverti XX veka (po materialam fonda Natsional’nogo Muzeya Respubliki Buryatiya). PhD Thesis. East Siberian State Academy of Culture and Arts. Ulan-Ude.

Batomunkueva, S.R. (2023) ‘Dialogue Between Authorities and Believers: Prehistory of Ivolginsky Datsan Foundation’, Humanitarian Vector, 18, 64–73.

Bazarov, A.A. (2014) ‘Indo-Tibetskaya filosofskaya kul’tura v Buryatii’, in I.R. Garry (ed. in chief), Buddizm v Istorii i Kul’ture Buryat, Ulan-Ude: Buryat-Mongol Nom, 134-155.

Boronoeva T.A., Balzhurova A.Zh. (2020) ‘Cultural Dialog Between the Religious Organization and Museum (The Experience of Implementing the Project «Preservation of the Historical Monument Ivolginsky Datsan “Khambyn Khuree”»)’, Sukachevskie Chteniya, 17, 128-133.

Charleux, I. (2010) ‘The making of Mongol Buddhist art and architecture. Artisans in Mongolia from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries’, in E. Eevr Djaltchinova-Malets (ed.), Meditation. The Art of Zanabazar and His School, Warsaw: State Ethnographic Museum, 59-106.

Chimitdorzhin, D.G. (2019) Buddizm v Rossii: Buryatiya XVIII-XXI vv. Volume I-II. Ulan-Ude: Respublikanskaya Tipografiya.

Ershova G. G. (2018) ‘Spiritual Feat in the History of Buddhism of Russia’, Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 64:4, 1156–1176.

Holland, E.C. (2014) ‘Buddhism in Russia: challenges and choices in the post-Soviet period’, Religion, State and Society, 42:4 , 389–402.

Morgan, D. (2017) ‘Material Analysis and the Study of Religion’, in T. Hutchings and J. Mckenzie (eds), Materiality and the Study of Religion. The Stuff of the Sacred, New York: Routledge, 14-32.

Syrtypova, S.D., Garmaeva, Kh. Zh., Bazarov, A.A. (2006) Buddiiskoe Knigopechatanie v Buryatii XIX-nachala XX v. Ulanbator.

Zalkind, E.M. (ed. in chief) (1972) Ocherki Istorii Kul’tury Buryatii. Volume I. Ulan-Ude: Buryat Book Publishing House.

Zhukovskaia, N. L. (2001) ‘The Revival of Buddhism in Buryatia Problems and Prospects’, Anthropology & Archeology of Eurasia, 39:4, 23-47.

Ekaterina Sobkovyak is a graduate of the Department of Tibetan-Mongolian Philology of the Saint-Petersburg State University, Russia, and the Department of Turkish Studies and Inner Asian Peoples of the Warsaw State University, Poland. She holds a PhD in the field of Central Asian cultural studies from the University of Bern, Switzerland. She is currently affiliated with the Institute for the Science of Religion of the University of Bern as an associated researcher. Her main area of interest, which she has devoted a part of her thesis to and published several articles on, is the Mongolian Buddhist monastic tradition and culture with a special emphasis on the study of Mongolian Buddhist monastic institutions.