Lincoln Cathedral

The Story of a Thousand Years of Christian Faith made Manifest

by Fern Dawson

Figure 1. Lincoln Cathedral, also known as Lincoln Minster, or the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln.

Cathedrals and churches express faith in many ways; from personal devotion to communal worship and, in more modern times, a devotion to the historic by being a visitor destination alongside their primary function of Christian worship. Through these original and later uses, collections have developed and evolved, creating unique and fascinating assemblages. Collections pose many questions for modern curators; identifying provenance, uses and hidden symbolism. The Cathedral has been the focal point of Christian worship and a guardian of historic artefacts long before the establishment of museums or, earlier, cabinets of curiosities. It has long been a beacon for many donated artefacts, especially those that would aid theological education. Through loss and renewal, Lincoln Cathedral’s collection has become one of the UK’s most significant collections.

Figure 2. Portrait of Dean Michael Honywood by Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen, c.1681. Wren Library, Lincoln Cathedral.

Lincoln Cathedral’s collection reflects the interests of prominent figures within its history. The Wren and Medieval Library owe much of their collection to the efforts of one man - Michael Honywood, Dean of Lincoln 1660-1681. As part of his effort to re-build the Cathedral in 1660, following his exile to the Continent and after the English Civil War, he gifted his private collection of books [1]. The original list, written by Dean Honywood in A catalogue of books bought for myselfe since my coming out of England, Jul. 6. st. n. 1643 [2], lists the books, with the final leaves used for entries of books sold, and books lent and to whom. Today the library holds 400 of the books positively identified as those brought by Dean Honywood. Some of the works collected include St Jerome’s 1468 Epistolae [3], De Voragine’s 1487 The Golden Legend [4], and Milton’s 1667 Paradise Lost [5]. By donating these items to Lincoln Cathedral and investing in a new Library designed by Mr Thomas, with the construction supervised by the famous Christopher Wren, Dean Honywood was re-establishing the Cathedral’s place as a centre for education and faith, which has been a core purpose since the building’s foundation. Further personal collections have been donated in more recent times including John Wilson, Cathleen Major and Dorothy Owen during the 20th and 21st centuries.

Figure 3. The Wren Library 2021- Lincoln Cathedral.

Figure 4. 1215 Magna Carta - Lincoln Cathedral - currently on display at Lincoln Castle.

The Cathedral’s Dean and Chapter archive has developed over the years through the governance of the Cathedral, including material such as accounts, court records, inventories and royal charters. The historic role of the Cathedral was as the centre of the county of Lincolnshire and the wider diocese, which originally was the largest Diocese in England, extending from the River Thames to the Humber Estuary. This large geographical reach has led to a vast, wide-reaching collection, illustrating the religious-political and administrative role of the Church. As a result of its role in governance, the Cathedral holds some of the most nationally and internationally significant items, most notably the 1215 Magna Carta [6] and 1217 Charter of the Forest [7]. The collection of royal charters tracks the rise and fall of monarchs since King Stephen, up to the current monarch Queen Elizabeth II. More ‘mundane’ archival material created purely through the work of people associated with the Cathedral brings to life the day-to-day running of the Cathedral through its history. These items include personal correspondence between clergy, bills, accounts, Chapter meeting records, sketches and early photographs. These seemingly everyday items are rare survivors and now form a crucial part of the Cathedral’s collection, bringing an understanding of the building and historic events, which otherwise would have been lost over time without the Cathedral’s historic administrative system.

The Cathedral building itself has generated a vast collection of artefacts from repair works, from damaged features removed from the main structure to ‘treasures’ hidden by craftsmen (these treasures include many items that can be dated, like coins). As well as the physical architectural features, there is the additional archival material held in the Works Archive that documents key features, repairs and alternations from 1829 to the present day. These documents chart the changes to the Cathedral’s architecture as well as the architects and craftspeople involved, including key figures: James Essex (1722-1784), John L Pearson (1817-1897) and Robert Godfrey (1918-1953). These records include photographs, adding greater depth to this archival collection.

Figure 5. Photograph of 26 Masons from Lincoln Cathedral’s Works Department, 1920s.

Figure 6. Roman Incense Burner from excavation, part of NLHF Lincoln Cathedral Connected project, 2018.

Another key element of the Cathedral’s collection has developed through archaeological excavation throughout the Cathedral Close and within buildings. Since the 1700s discoveries have included a number of significant artefacts such as grave goods of the founding Bishops; Bishop Grosseteste, Bishop Sutton and Bishop Gravesend. The d’Eyncourt plaque, one of the Cathedral’s most significant artefacts, dating from the 11th century, illustrates the link between the Cathedral and William the Conqueror. More recent archaeological excavations have taken place as part of the development of the new visitor centre, situated on the north side of the Cathedral and attached to the late 13th century Cloister. This excavation furthered the Cathedral’s knowledge of early Roman occupation of the site, with artefacts including an incense burner with pie crust decoration, believed to be a near unique intact example. Excavations have brought further understanding not only of the artefacts and the architecture of the Cathedral site but also of the individuals associated with it. As the Cathedral grounds have been used as a burial place, there have been many remains discovered, recorded and reinterred. These remains have given an insight into the lives of the people associated with the Cathedral; one example of this was a small skull excavated in the Nettleyard in 2003. Analysis of the skull revealed that this child died around the age of 13 years and lived in the late 13th century, before the construction of the Cloister. A further skeleton from an excavation of the West Front in 2020 was the subject of a facial reconstruction. Analysis of the skeleton has confirmed that the person was a male, and that he was approximately 169cm tall and died between the ages of 35 and 45 years old. The associated grave goods interred with the body suggested that the person was also a priest, with a pewter chalice and paten. The report shows that these objects were plain in style, and similar examples have been dated back to as far as the 12th and 13th centuries.

Figure 7. The Sculpture of the Blessed Virgin Mary, by Aidan Hart, 2014.

The development of the Cathedral’s modern collection has continued with artefacts acquired through the continuance of faith and supporting traditional skills, through the Cathedral’s own Works Department, Needlework Guild and initiatives such as the Artist in Residence scheme. Many of these items are used within the Cathedral on a daily basis such as the plate by Antony Elson, commissioned in 2007, which represents the continuation of tradition and the significance of the swan as a symbol of St Hugh of Lincoln. Other art pieces express older traditions including the Gilbertine Pots designed by Robin Welch in 1985, representing St Gilbert and the monastic order of Gilbertines, using candle pots that signify the monks and nuns. The significance of these artefacts is their daily use as part of the continuance of prayer and meditation within the Cathedral, which is furthered by their positioning in the East End. One piece that brings together the founding Catholic tradition with the now Anglican tradition of the Cathedral, is the statue of the Virgin Mary, created by Aidan Hart in 2014. This religious icon encapsulates both traditional symbolism and historic craft and is held within one of the Cathedral’s historic chantry chapels at the East End of the Cathedral.

‘As an icon carver and painter, I believe that the ultimate role of liturgical art is to be a means of uniting heaven and earth, God and man, eternity and the present. I would therefore aim to make this sculpture of the Virgin Mary of Lincoln a fruit of the incarnation, itself rooted both in place (the chapel, the cathedral, Lincoln, the local materials) and in God. I would chose a style of carving that would reflect a spiritual view of the world, that would be timeless. To aid this I would research the existing Romanesque and Gothic works within the cathedral, as well as drawing on my existing knowledge of other western and eastern iconography’.

Aidan Hart [8]

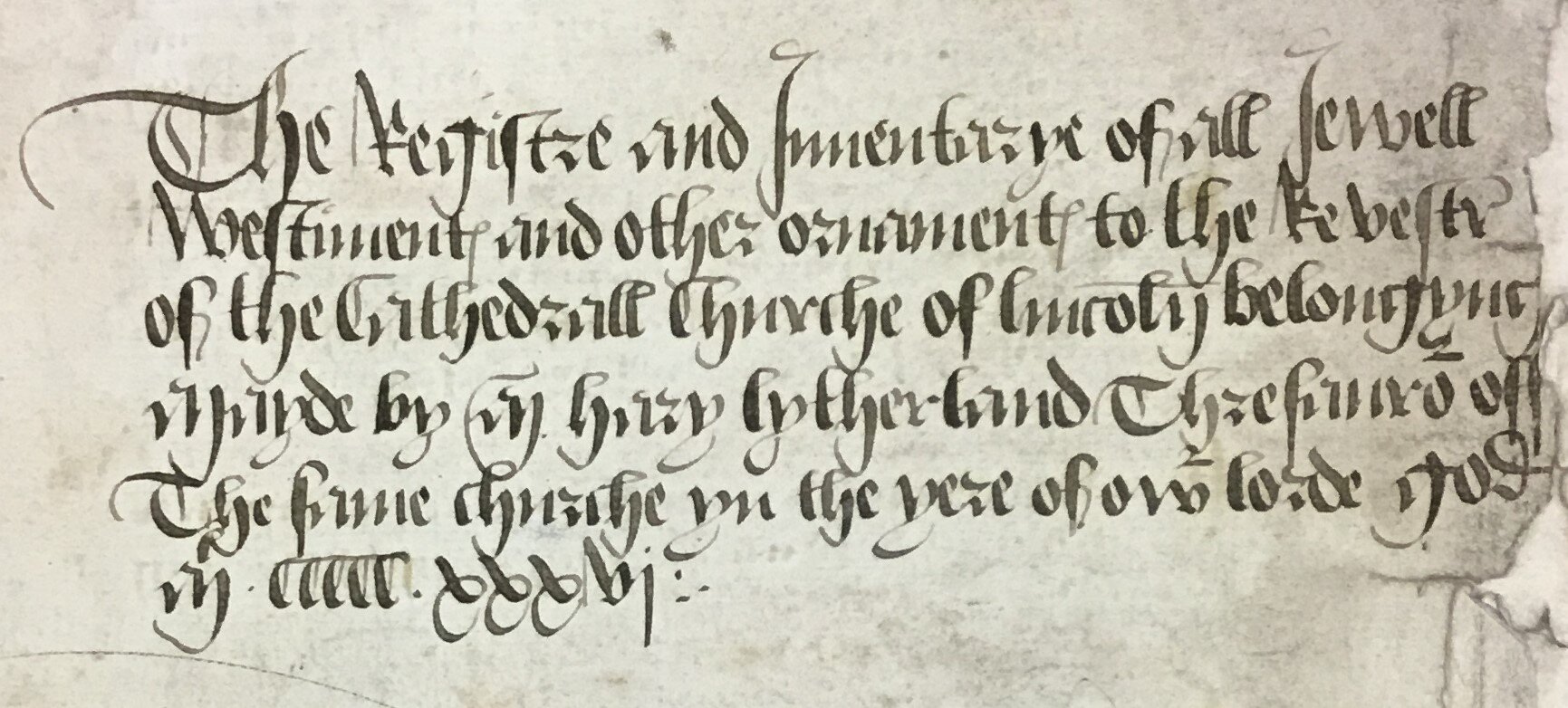

The Cathedral has been through seismic disruptions, including an actual earthquake in 1185, as well as dramatic political changes which have impacted all church and cathedral collections across England. The most significant of these changes were the Reformation in the 16th century and the English Civil War (1642–1651). These events damaged the architecture of the building and decimated centuries-old collections, necessitating the creation of replacements, in many cases to a far lesser extent and quality to the items lost. The 1536 inventory, written by the then Treasurer John Litherland lists items that were removed during the Reformation [9]. The inventory gives an insight into the now lost artefacts including vestments, plate and relics. The relics held by cathedrals and churches became the basis for many pilgrimages, which in turn established these Christian places of worship as famous sites that gained the patronage of donors, which led to the creation of many of the artefacts listed. Relics inspired worship and devotion as well as patronage, and furthered the belief in indulgences. Many items adorned Chantry chapels. The Cathedral building itself has been shaped by such relics, including the Shrine of St Hugh, which due to its popularity with pilgrims made it necessary to extend the East End of the Cathedral.

Figure 8. 1536 Inventory. Listing all valuables held by the Cathedral before removal by the agents of Henry VIII - Lincoln Cathedral.

Like the Reformation, the English Civil War (1642–1651) left visible marks on the Cathedral, with the decimation of key shrines and features, many of which were recorded by Sir William Dugdale (1605-1686) author of Monasticon Anglicanum 1655–1673 [10]. Dugdale is most famous as an English antiquary and herald. As a scholar he was influential in the development of medieval history as an academic subject. According to his later account, in 1641 Sir Christopher Hatton [11], foreseeing the English Civil War and dreading the ruin and spoliation of the Church, commissioned Dugdale to make exact drafts of all the monuments in Westminster Abbey and the principal churches in England. Unfortunately, unlike the 1536 inventory these documents do not give as great detail of the smaller portable artefacts, so many lost items remain unknown. Later Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733-1794) a Swiss born landscape artist would capture images of the Cathedral, including the opening of the tomb of Little Hugh [12]. These vital documents leave clues, which illustrate some of the most dramatic events and their direct impact on the Cathedral’s collection.

Figure 9. 19th-century stained glass depicting Parliamentarian troops ransacking Lincoln Cathedral, The Chapter House, Lincoln Cathedral.

A lesser but also important factor in the development of the Cathedral’s collection has been the impact of theft, including more recently the theft of plate in 1805 and 1950, where existing pieces of Cathedral plate were removed. The 1805 collection was never recovered and is believed to have been melted down and sold on. Through this theft a new set of church plate was commissioned and donated by Dean Gordon in 1824 [13], again renewing the Cathedral’s collection.

The development of the Cathedral’s collection has been shaped by many external factors and events, though the collection has largely remained accessible to only the few. However, a greater awareness of cathedrals and churches as treasure houses has developed since the nineteenth century; this is illustrated in legislation and public societies, although initially focusing on the architectural significance rather than on portable collections. In 1877 the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) was founded by William Morris, primarily to resist the 19th century restorations of medieval churches that were seen as dishonest. Their arguments for preservation would include vernacular buildings of fine craftsmanship as well as major monuments. Following this came the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882 then the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1922. Many legislations followed, culminating in the 1999 Cathedral Measure (now superseded by the Cathedral Measure 2020), which included collections in a more overt way. Alongside these legal developments, Lincoln Cathedral has continually improved the care and understanding of its collection, improving both public and academic access. During the early 1960s Lincoln Cathedral’s Treasury was created as the first accessible Treasury established in England, in which the 1215 Magna Carta was originally displayed. The Cathedral’s Wren and Medieval Library opened to the general public as part of a general visit, while further establishing links with academics and higher education.

Figure 9. 12th Century 2nd Chapter Seal, Lincoln Cathedral.

In more recent times the Cathedral has undertaken a once in a lifetime project to further access to the collection. In 2013 the Cathedral began the development of a project to create dedicated display spaces that would allow for sensitive and significant artefacts to be displayed, including the internationally significant Romanesque Frieze. As with many churches and cathedrals, the need to further develop a visitor offer, which could help to sustain the repair and care of the building and vast collections, became a driving factor. Many cathedrals and churches had shared their collection through loans to established museums; however, removing these deeply personal and context-rich artefacts can be argued to have lessened their interpretation. Again external funding, as with patronage in the medieval period, became a way to develop these ambitions to showcase items in their original context. One such funder, the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF), since 1995 has invested more than £970m in places of worship across the UK. This development has not only widened physical access to collections but has professionalised the cathedrals’ collection teams establishing new roles or reassessing existing remits. For example, in 2015 York Minster became the first Museum Accredited cathedral, many others are wanting to follow this route. At Lincoln Cathedral, the NLHF project - Lincoln Cathedral Connected - was awarded its first round of funding in 2015 and is due for completion by March 2022. This project has created new dedicated display spaces that celebrate and enable different artefacts to be displayed, the majority of which are completely unknown and unseen by the public since their creation. Through this work, the entirety of the collection has become an active entity, under constant review and investigation. Discoveries have been made through preliminary audits, most notably the discovery of three seal matrices, including the 12th century Second Chapter Seal of Lincoln Cathedral, one of only two examples known to be in existence and the only example still held within its original Cathedral. The other, from Chichester Cathedral, is held at the British Museum. This type of discovery is being replicated across many cathedrals and churches as collections become more accessible.

Lincoln Cathedral’s collection not only represents the glory of god, but the ever developing nature of Christian faith and society. Its trajectory has followed national and local events, repeating a cycle of loss and renewal, but with the constant purpose of serving the Christian community.

The new exhibition gallery at Lincoln Cathedral is due to be opened in Autumn/Winter 2021, with a series of changing exhibitions exploring different aspects of the Cathedral collection, across historical and more contemporary artefacts. Access to the collection is also available online through https://archive.lincolncathedral.com/. The site is regularly updated with new artefacts, information and images. If you wish to access the collection as a researcher please contact Julie.Taylor@lincolncathedral.com for Library collections and Fern.Dawson@lincolncathedral.com for the 3D portable collection, Works Archive and D&C Archive.

Notes

1 Draft Audit- Dean and Chapter of Lincoln, 1682 '. . . paid for removing the late Deans bookes into the Library 00-07-09'- Ref D&C/Bj/4/1

2 'A catalogue of books bought for myselfe since my coming out of England, Jul. 6. st. n. 1643'2. Ref Lincoln MS 276

3 Jerome, St. (1468) Epistolae. Rome: Conradus Sweynhem and Arnoldus Pannartz . Ref B 01 07

4 Voragine, J. de (1487) The Golden Legend. Westminster: William Caxton. Ref B 03 01

5 Milton, J. (1667) Paradise Lost. Ref A 03 10

6 Magna Carta 1215.Ref D&C/A/1/1B/45

7 Charter of the Forest. Ref D&C/A/1/1B/46

8 The Genesis of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Lincoln Sculpture and Liturgical Art in Britain- A talk to the College of Canons of Lincoln Cathedral on the Feast of St Hugh, Tuesday 17 November 2015. Ref https://aidanharticons.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Lincoln-Our-Lady-of-Lincoln.pdf

9 1536 Inventory; Henry Litherland's inventory of Cathedral treasures. Ref A/2/15/1-3

10 Caley, J. and Ellis, H. (editors) (1846) Monasticum Anglicanum : a history of the abbies and other monasteries, hospitals, frieries, and cathedrals and collegiate churches, with their dependencies in England and Wales ... originally published in Latin by Sir William Dugdale 6 vols. London: James Bohn. Ref 271 DUG

11 W. Hamper, Life, Diary and Corresp. of Sir William Dugdale, 170-80, passim.

12 Tomb of Little St. Hugh- Sketch by Samuel Grimm. Ref MS 280

13 Plate gifted by Dean Gordon. Ref Chalices PS 34, Patens PS 35, Dishes PS 33 and Flagons PS 32