St Martin-in-the-Fields, London

By Jonathan Evens

Altar by Shirazeh Houshiary and Pip Horne, paschal and altar candleholders and processional cross by Brian Catling.

Introduction

At the beginning of the twentieth century a perceived disconnect existed between the Church and modern artists. A group of artists, clergy and philosophers including Maurice Denis, Jacques Maritain, Albert Gleizes, Marie-Alain Couturier in France, and Eric Gill, George Bell and Walter Hussey in the UK made it their life’s work to reconnect the Church with modern art. To do this through church commissions, to differing degrees, they worked both with artists who were Christians and who primarily focused their work on church decoration and also with artists who were reckoned to be contemporary masters, regardless of whether or not they practised the faith. Through their work and influence there has been a renewal of religious art in Europe during the twentieth century and a renewal of church commissioning.

Artworks commissioned for or loaned, from the 1950s onwards, to St Martin-in-the-Fields in the centre of London have been part of these wider trends and debates. The parish Church of St Martin-in-the-Fields is regarded as the masterpiece of the distinguished 18th century architect James Gibbs and one of the country’s finest historic churches. Gibbs' design for St Martin’s, inspired by the Italian Baroque, has become one of the most imitated architectural models in the world, and the inspiration for churches throughout much of North America and the Commonwealth. However, by 2003 the church and its site were in need of substantial renewal.

This Renewal Programme cost £36 million. The overall design provided a sequence of beautiful, practical and inspirational spaces to serve the community, visitors and those in need, while also ensuring the life and sustainability of the church. In order to complement the Renewal Programme, St Martin’s also embarked on a significant programme of art commissions. These have attracted much interest and gained widespread acclaim. Some artworks, prior to the Renewal Programme, came to St Martin’s because of connections between the church and the artists involved, others as commissions for acclaimed contemporary artists with no other connection to the church. Initially, modern commissions at St Martin’s were occasional and opportunistic, while from the Renewal Programme onwards they became intentional and part of a strategic plan.

Since the Renewal Programme was completed in 2008, the church has broadened its engagement with the visual arts through a programme of temporary exhibitions and by working with artists and craftspeople within the congregation. The experience here, therefore, demonstrates a ‘mixed economy’; sometimes engaging, as Couturier and Hussey did (see further below), with artists perceived to be among the best of our time, whilst also working with artists with whom the church has had connections through the congregation and wider community.

In 2016, the church celebrated its 15-year arts programme with a Thanksgiving Service at which two new commissions by Giampaolo Babetto and Brian Catling were dedicated. The greatest cause for thanksgiving was the overall success of the Renewal Programme and its programme of commissions in complementing and supplementing Gibbs’ innovative architectural design. This is generally held to have been a remarkable achievement and one that invites further analysis.

Commissions

In 2004, an Arts Advisory Panel, chaired by Sir Nicholas Goodison and advised by Modus Operandi Arts Consultants, was formed to advise the Parochial Church Council (PCC) on art commissions and loans. Goodison came to chair the Panel at the invitation of Nick Holtam, then Vicar of St Martin's (1995-2011), later Bishop of Salisbury. The task of the panel was to select artists for projects agreed by the PCC and to offer proposals for discussion. Modus Operandi were appointed to create an Art Strategy for the church and to act as mediators between artists, clients, design professionals and the public, in order to facilitate the selection of artists and the successful coordination of commissioned works.

Parameter by Mark Francis.

The first written strategy for art commissions in and around St Martin's was devised in 2005. Its overarching vision provided the rationale and criteria for future commissioning. It advocated involving artists from various disciplines in many aspects of the building project, both within the historic fabric and in the new external public spaces. Interpretation of historical material and commissioned artworks within the interior public spaces was also recommended, as was the notion of temporary or loaned artworks, and the commissioning of musical composition and poetry.

With advice from the panel and assisted by Modus Operandi, the PCC commissioned the following: a Christmas crib by Tomoaki Suzuki; an Andrew Motion poem realised by lettercutter Tom Perkins for the Light-well balustrade; a new East Window and a new altar by Shirazeh Houshiary and Pip Horne; furniture for the Sanctuary and also the Dick Sheppard Chapel designed by Eric Parry; metalwork for the Dick Sheppard Chapel by Giampaolo Babetto including candle holders, and a chalice and paten; and altar and paschal candleholder for the main church together with a processional cross by Brian Catling. In addition, certain loans were acquired, including Abdu, a monumental tapestry by Gerhard Richter for the Dick Sheppard Chapel, and, in the Light-well, Shadow No. 66 (a painted triptych) by Brad Lahore and Parameter, a painting by Mark Francis, replacing the earlier loan of a painting by Fiona Rae.

St Martin and the Beggar by James Butler.

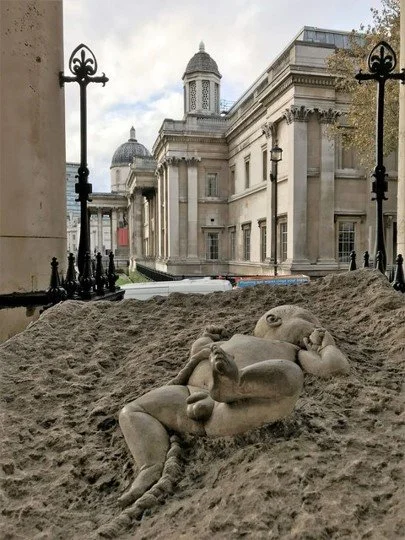

In the Beginning by Mike Chapman.

Earlier commissions in the church have now also become complementary to this programme. They include: St Martin and the Beggar by James Butler; Jacaranda work sculptures by John Chikerema; The Living South Africa Memorial, a sculpture in bronze by Chaim Stephenson; In the Beginning, a sculpture marking the new millennium by Mike Chapman; the gift of a Heritage Edition of The St John's Bible, a magnificent contemporary illuminated Bible; and the more recent commissioning of a Lampedusa Cross from Francesco Tuccio. In addition, the church continues to mount temporary exhibitions and to display work by artists and craftspeople from the congregation.

Jacaranda work sculptures by John Chikerema.

Butler’s sculpture of St Martin and the Beggar was made in 1951 when he was a student at St Martin’s School of Art. Chikerema’s sculptures of the Holy Family come from the school associated with the Driefontein Mission near Masvingo in Zimbabwe established by the Swiss Bethlehem Fathers. Chapman’s image of the Christ-child is carved in a 4.5 tonne block of Portland Stone which is now permanently on display at the entrance to the church. The opening text from the Gospel of John is inscribed around Chapman’s sculpture: "In the beginning was the word and the word became flesh and lived among us." Stephenson’s sculpture was inspired by photographer Sam Nzima's iconic picture of the shooting of teenager Hector Pieterson in Soweto in 1976 and reflected the way in which the steps of St Martin’s became a place of vigil against apartheid.

The East Window and altar by Shirazeh Houshiary and Pip Horne, candleholders and processional cross by Brian Catling, together with the temporary display of 'The Blind Jesus (No one belongs here more than you)' by Alan Stewart.

The glass panels of Houshiary‘s East Window graduate from a periphery of more transparent glass to a denser, whiter centre. The central ellipse itself is lightly etched, and lit in such a way as to form a focal point of light visible internally and externally. Her minimal monochromatic design had its starting point in the story of ‘Jacob’s Ladder’, a story which has had a continuous thread of resonance for St Martin’s. Catling’s Processional Cross references a ‘cross of poverty’. The starting point is two pieces of wood humbly tied together by a length of string; a third piece of wood hanging from the centre provides an allusion to St Martin tearing his cloak in two and giving half to a beggar.

Theological underpinning

Eric Parry, architect for the Renewal Programme, rightly argues that St Martin-in-the-Fields has set a model example of “the lasting significance that the visual arts can bring to an architectural setting through the depth of meaning it [art] can reveal” (‘The Art of St Martin-in-the-Fields’ by Modus Operandi Art Consultants, 2016). Key to this achievement has been the effective use of strategies, advisory panel and an art consultant, all united with the aim of achieving a balance of interests, between prophetic, priestly and kingly art and the location, history and ethos of St Martin's. As a result, the theology and history of St Martin's has underpinned the programme.

Sam Wells, the current Vicar of St Martin-in-the-Fields, has reflected theologically on the art of St Martin’s:

“One may fruitfully think of art and faith under three headings – the Old Testament offices of prophet, priest and king coalesced in Jesus. (1) Prophets hold a mirror up to society or individuals and point out glories, failures, anomalies, and mysteries. Prophets challenge, reconfigure, expose, highlight, ridicule, and shock. So do artists. (2) Priests seek to make every experience and every material thing an icon, through which the observer can look and see the ultimate truth, profound wisdom, the heart of God. Artists are high priests of creation: they gather around them all the fruits of creation, just as a priest does around an altar, and order those gifts in such a way as to show the divine in the human and earthly. (3) Kingly art is art that thrills, and delights, and excites, inspires, and enthrals – art that stretches our imaginations to their limit in exaltation and awe and delirious rejoicing, and raises our sights to power and glory. It is fundamentally art that enjoys, cherishes and highlights the materiality and visibility of life.”

Prophetic art, he argues, is found in The Living South Africa Memorial, which evokes the suffering of the anti-Apartheid struggle. He continues:

“We behold priestly art, like the processional cross, agonising, rugged, torn, twisted, fearful; and yet in this tortured, terrible, trembling sight we see glory, wonder, life, hope, freedom, truth. The most obvious dimension of kingly art at St Martin-in-the-Fields is the building itself. It's a huge, royal, political and theological statement. And these prophetic, priestly and kingly dimensions are brought together in the East Window. Its skewedness is edgy, its cross-shaped invitation is holy, and its glorious transparency (especially in the early morning when the sun pours through it) is kingly.”

(‘The Art of St Martin-in-the-Fields’ by Modus Operandi Art Consultants, 2016).

Wells argues that the art of St Martin’s reflects this threefold diversity of heritage, identity, and vocation and must continue to balance the three into the future, as to become too strongly identified with one of the three aspects would endanger the good regard of vital elements of the St Martin’s community.

On Sunday 13 November 2016 St Martin’s celebrated its 15-year programme of art commissions and loans with a reception for those who have been involved (including Vivien Lovell of Modus Operandi, who curated the programme, and Sir Nicholas Goodison), a tour of the artworks, an exhibition by artists and craftspeople from the congregation, and a service in which recent metalwork commissions by Babetto and Catling were dedicated.

This service included reflections from St Martin’s clergy on the Babetto and Catling commissions, a survey by Vivien Lovell of the 15-year programme, a sermon from Sam Wells connecting the Arts to Christian praxis, and prayers of thanksgiving for creative skill and insight from artists and craftspeople in the St Martin’s congregation.

Ali Lyon (one of the craftspeople at St Martin’s) led the congregation in a prayer which makes the claim that the heavens are telling the glory of God, and so are the many artworks at St Martin’s. Her prayer for this service was eloquent in its belief that there is a real and continuing engagement between the visual arts and Christianity, of which the art of St Martin-in-the-Fields is part:

‘Your story, God, is shown in wood, stone, yarn, metal, string, glass, paint, fabric. Your glory, God, is told in images from birth to death, and beyond; from outside to inside, and back out again; from light to dark, from dark to light. Your challenge, God, is given in words and in wordlessness. Your glory, God, is shown in colour, shine, shadow, shape, space, form. Your story, God, is shared by those who dream, those who create, those who install, those who fund, those who support, those who look, those who advise. And so, we give thanks for the materials, the skills, the artworks, that illuminate God, that draw people in and send people out. And we pray that all these creations will continue to bless this place and all the people who come here.’

The close fit between St Martin's theological, historical and artistic ethos has drawn many into a deeper reflection and contemplation about the meaning of faith and relationship with God. Trafalgar Square is, of course, well-known as the location for the world-famous art collections in the National Portrait Gallery and National Gallery, as well as the contemporary Fourth Plinth commissions, but the art of St Martin-in-the-Fields now creates a complementary and special space for art lovers and worshippers alike.

Chichester Cathedral and other examples

As noted earlier, church commissions in the UK including those at St Martin-in-the-Fields drew on aspects of the legacy created by Canon Walter Hussey while Vicar of St Matthew’s Northampton and the Dean of Chichester Cathedral. Hussey wrote in a brief for the Marc Chagall window commissioned for Chichester in a period from 1969 to 1978 and based on Psalm 150 — the conclusion to Hussey’s remarkable series of commissions: “It has been the great enthusiasm of my life and work to commission for the Church the very best artists I could, in painting, in sculpture, in music and in literature.”

Bishop George Bell strongly supported the appointment of Walter Hussey as dean of Chichester Cathedral to take forward the commissioning programme he had initiated there as part of his wider programme to reinvigorate the Church’s patronage of the arts. From the 1920’s to the 1970’s, other Anglican clergy, such as Victor Kenna, Moelwyn Merchant, and Bernard Walke, played their part in this wider work of reinvigoration, but it is Hussey’s commissions of William Albright, W. H. Auden, Leonard Bernstein, Benjamin Britten, Chagall, Cecil Collins, Gerald Finzi, Henry Moore, Norman Nicholson, John Piper, Ceri Richards, John Skelton, Graham Sutherland, Michael Tippett, and William Walton that stand out, in the fields of literature, music, and the visual arts, as truly significant. For his commissions at St. Matthew’s and Chichester Cathedral, Kenneth Clark memorably described Hussey as “the last great patron of art in the Church of England.”

Certainly, the mix of commissions at Chichester Cathedral — from the “riot of colour and symbol” in the Piper tapestry to the glow of Hans Feibusch’s tender Baptism, the harmonious whole that is the Icon of the Divine Light by Cecil Collins to the fractured energies of Ursula Benker-Schirmer’s tapestry for the Shrine of St. Richard — while not all Hussey commissions genuinely invigorate and beautify the cathedral while introducing variety and intrigue into the experience of visiting and worshipping there. Hussey believed that “true artists of all sorts, as creators of some of the most worthwhile of man’s work, are well adapted to express man’s worship of God.” When this is done consciously, he says, “the beauty and strength of their work can draw others to share to some extent their vision.”

Building on the twentieth century achievements of Hussey and his French counterpart, Marie-Alain Couturier, among others, has led to a real and exciting upsurge in church commissions which takes the story of commissioning contemporary art for British churches up to the present day. As one example among many, the 2010 exhibition Commission at Wallspace Gallery began with Henry Moore’s remarkable, and at the time highly controversial, altar for St Stephen Walbrook, before going on to the work of 14 artists who had taken on the challenge of a permanent work for a religious space. Major commissions for the Lumen Centre URC church and St Martin-in-the-Fields, and Tracey Emin’s neon artwork for Liverpool Anglican Cathedral were all represented. Other artists featuring in Commission included Craigie Aitchison, Mark Cazalet, Stephen Cox, Chris Gollon, Shirazeh Houshiary, Iain McKillop, Rona Smith and Alison Watt.

Nicholas Holtam is among those who have argued that there has been a renaissance in the relationship between Christianity and the arts, of which the commissions at St Martin’s are part. Based on his experience, Holtam suggested that there is an enormous willingness on the part of artists to explore meaning and faith creatively and with imagination. He argued that whilst there might be safety for the Church in accepting only the work of Christian artists, the more important engagement is with good art that respects its Christian context. It makes us bigger people and deepens both our cultural life and the life of faith.

All the photographs in this essay were taken by Revd. Jonathan Evens.

Bibliography

‘The Art of St Martin-in-the-Fields’ by Modus Operandi Art Consultants, 2016.

‘The Art of St Martin In The Fields’ by Revd Jonathan Evens, Artlyst, November 2016 - https://artlyst.com/features/the-art-of-st-martin-in-the-fields-by-revd-jonathan-evens/

‘New art at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London’ by Jonathan Evens, Art & Christianity, Spring 2017 -https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=LitRC&u=googlescholar&id=GALE|A490551178&v=2.1&it=r&sid=googleScholar&asid=c5c4eb6d

‘Modus Operandi What Makes Successful Public Art: Vivien Lovell Interviewed’ by Revd Jonathan Evens, Artlyst, April 2021 - https://artlyst.com/features/modus-operandi-successful-public-art-vivien-lovell-interviewed-revd-jonathan-evens/

‘Contemporary art in British churches’ edited by Laura Moffatt and Eileen Daly, Art+Christianity, 2010.

‘Church and Patronage in 20th Century Britain: Walter Hussey and the Arts’ by Peter Webster, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Jonathan Evens is Team Rector for Wickford and Runwell. He was previously Associate Vicar for HeartEdge at St Martin-in-the-Fields, where he developed HeartEdge as an international and ecumenical network of churches engaging congregations with culture, compassion and commerce. In this time, he also developed a range of arts initiatives at St Martin’s and St Stephen Walbrook, a church in the City of London where he was Priest-in-charge for three years, as well as supporting St Martin’s in its ongoing partnerships around disability and church. He has been ordained for nineteen years and in that time has had involvement in setting up: the Barking & Dagenham Faith Forum; commission4mission, an artist’s collective; and Seven Kings Sophia Hub, a support service for business and community start-ups. He is co-author of ‘The Secret Chord’ (Lulu, 2012), an impassioned study of the role of music in cultural life written through the prism of Christian belief, and writes regularly on the visual arts for national arts and church media including Artlyst, ArtWay and Church Times. Before being ordained Jonathan worked in the Civil Service forming partnerships to support disabled people in finding or retaining work.