The Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, Ukraine

By Alice Isabella Sullivan

“In Kiev [Kyiv] I lived with the dead, [princes] Vladimir and Iziaslav completely possessed my imagination … Nature is splendid; plants, poplars, winegrapes … In addition, there is the holiness of ruins and the darkness of caves. How shuddering it is to walk in the darkness of the Caves Monastery…”

— Russian poet Alexander Griboyedov (1825) (Bilenky, 2018, p. 44)

The Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra – also known as the Kyivan Caves Monastery – is the oldest monastic complex of Rus. Medieval primary texts reveal that it was founded in 1050/1051 (6559, according to the Byzantine calendar) by a man from Liubech named Anthony. He had traveled to a certain “Holy Mount” – either Mount Athos in Greece or the Holy Mountain Monastery at Zymne in Volhynia (Thomson, 1995, pp. 637–68) – and upon his return to Kyiv, wandered the land in search of an ideal retreat from the world. Eventually, this divinely inspired monk found a spot in a cave atop a mount, overlooking the Dnieper River, some distance from the city center of Kyiv. There, Anthony settled in prayer and devotion, eventually establishing a monastic community (Lilienfeld, 1993, p. 63; Lewin, 1987).

General view of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The early history of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra is found in three key textual sources: the Primary Chronicle, the Life of Theodosius, and the Epistles of Simon and Polycarp (Cross and Sherbowitz-Wetzor, 1953, pp. 139–42).

One of the earliest icons of Rus, the thirteenth-century image known as “Our Lady of the Caves,” shows the Theotokos (Mother of God) at the center with the Christ Child on her lap against a gold background. To either side of the holy duo stand Saints Anthony and Theodosius. Both are hailed as early founders of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra (Bosley, 1980). Theodosius was the third abbot of the monastery, and the community grew under his guidance. He even established the Typikon that was intended to inform monastic life. He modeled this text on the famous eighth-century Typikon of the Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople.

The icon of “Our Lady of the Caves” with Saints Anthony and Theodosius, thirteenth century, now in the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

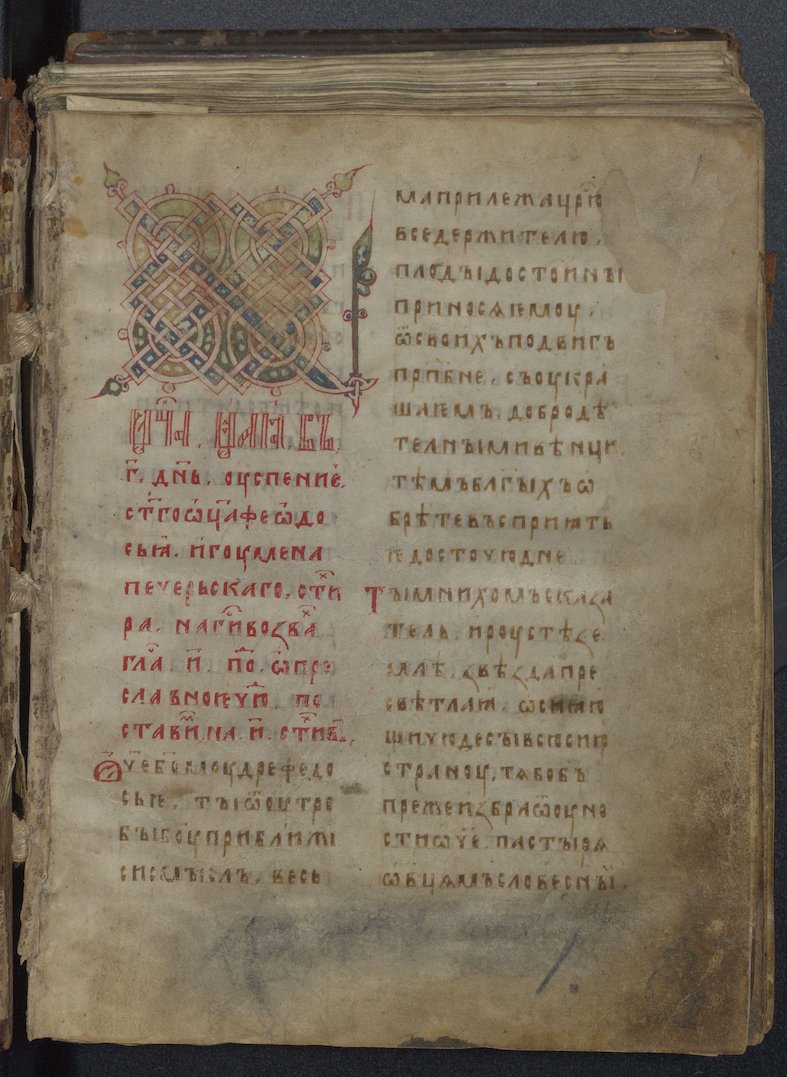

Other noteworthy medieval texts associated with the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra include the Kyivan Caves Paterikon (Heppell, 2011; Prestel, 1998; Prestel, 2017; Jusupović, 2022). Dating to the early thirteenth century, this text details the long and rich history of the monastery, including hagiographic writings about the lives of holy monks (Walton, 2022). Such a text would have offered instruction, while preserving the memory of the monastery and its community over time.

A folio from the Kyivan Caves Paterikon, written in the thirteenth century. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The important early icon of Saints Anthony and Theodosius connected with the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra is now housed in the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. Its journey away from Kyiv is representative of the dispersed cultural heritage of Kyivan Rus in Russia and other international collections, primarily due to the military and cultural conflicts of the twentieth century.

Throughout its long history, the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra was home to vibrant collections of icons, textiles, metalwork, woodwork, relics, books, prints, and much more. These collections grew in time through gifts, exchanges, donations, and objects produced in local workshops, demonstrating the piety of patrons, the connections of the monastery across the Christian cultural spheres, as well as the skills of local artists, craftsmen, and scribes.

Objects from these collections had been in use, on display, or stored in the various buildings of the fortified monastic complex over the centuries. The repositories included the main cathedral of the Dormition, which was first built in the eleventh century (1073) according to Byzantine design and decorative principles. Unfortunately, the cathedral was destroyed in November 1941 during World War II. The current building was begun in 1995 and consecrated in 2000. Among the many treasures of the former cathedral was a miracle-working icon of the Dormition of the Virgin, related to the dedication of the church. It supposedly stood above the entrance to the cathedral. Although now destroyed, the new church displays a nineteenth-century copy of this dedicatory icon.

View of the modern cathedral of the Dormition, Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The cathedral’s collection also included another noteworthy medieval icon. It shows the Virgin Eleousa (or Virgin of Tenderness) holding the Christ Child, and gently touching her cheek to his in a gesture of affection (Grimsted, 2013, p. 60, fig. 10). This twelfth-century icon is also known as the “Ihorivska Icon” and emulates in its iconography the famous “Virgin of Vladimir” – the Byzantine icon that arrived in Kyivan Rus likely as a diplomatic gift sometime during the first half of the twelfth century. As it was the custom in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the icon of the Virgin and Child from the Dormition cathedral received a lavish metalwork revetment, which was later discovered in the ruins of the destroyed cathedral (Grimsted, 2013, p. 71, fig. 13).

Other key buildings of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra complex include the Holy Trinity Church. Dating to the first decade of the twelfth century, the church became the main katholikon of the monastery after the destruction of the Dormition cathedral. Other churches date to the seventeenth century, including the church of Saint Anne’s Conception (1679), the church of the Nativity (1696), the church of the Resurrection (1696), and All Saints’ church (1696). In addition, a great belfry was constructed between 1731 and 1744. Rising 96 meters in height, the tower houses a library, a large clock, and three of its original large bells.

The Great Belfry of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra and one of its original bells. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

One of the original bells of the Great Belfry. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

But perhaps the most noteworthy aspect of the monastic complex is the vast underground network of caves that preserves the tombs of the holy monks and important figures associated with the monastery, including Saint Anthony. In fact, the name of the monastery, “Pechersk” derives from the Ukrainian word for “caves”/“pechery”. This labyrinth of underground passages once offered a retreat from the world for the holy men who lived and prayed at the monastery; now it serves as eternal resting places and sites of memory. “Despite the fact that the Caves Monastery was located close to Kiev [Kyiv], and not in the traditional desert (eremos), the symbolic value of the crypts/caves as a place apart from the world (kosmos) is a major feature of the Caves Monastery founding stories” (Prestel, 1998, p. 571). Today, the caves can be visited, serving as a key site in the spiritual economy and tourism of the region. Each year, visitors and pilgrims make their way through these exceptional holy caves that safeguard some of the most important relics of Christian Rus and Eastern Orthodoxy. These sites offer special and otherworldly experiences that bring one closer to the divine.

Although the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra was separated from the world, and physically protected by its fortification walls, it was still closely intertwined with its surroundings and Kyivan society (Prestel, 2006). Throughout its long history, the monastery benefited from support from local rulers and leaders, especially those tied to the princely court in Kyiv. In addition, it is known that women contributed to the monastery. For example, the widow of Gleb Vseslavich of Minsk (who funded the refectory of the Lavra in 1108) was acknowledged in a special way within the monastery and in the surviving records. The main Kyivan Chronicle records a lengthy eulogy for this royal woman upon her death on 3 January 1158 (Garcia de la Puente, 2012). She was then buried in the monastery near the tomb of Saint Theodosius. Her contributions to the monastery survive in the local collections and archives.

The material and textual evidence of the Lavra is preserved in various buildings of the monastic complex, which have been repurposed after the monastery was converted into a museum in 1926. At that time, the it was renamed the Kyiv-Pechersk Historical and Cultural State Reserve (All-Ukrainian Museum Town). In 1990, the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra was designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

Within the complex, one can find today the Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine, the Museum of Ukrainian Decorative Art, the State Historical Library, the Theater and Film Arts Museum, and the Book and Print History Museum, among others. For example, the Museum of Ukrainian Decorative Art is housed in the former residence of the Metropolitan and nearby structures. Its collection, established in 1899, contains 79,000 objects of Ukrainian folk decorative art from the fifteenth century to the present. These include folk costumes from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, beadwork and glassware, wood carvings, as well as paintings by renowned local artists. The Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine was instituted in 1981 in the guest house of the Lavra (built ca. 1755) – a building that also served as a school and a Women’s Theological Seminary. The museum was removed from that building in 2003 (Cybriwsky, 2018, p. 57). In addition to religious objects, the museum preserved the so-called Martynivka Treasure, which contains 116 silver objects dating to the sixth-seventh centuries. These were discovered in the village of Martynivka, Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine, in 1909. Part of the collection is now in the British Museum.

Examples of early medieval metalwork discovered in 1909 as part of the Martynivka Treasure. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

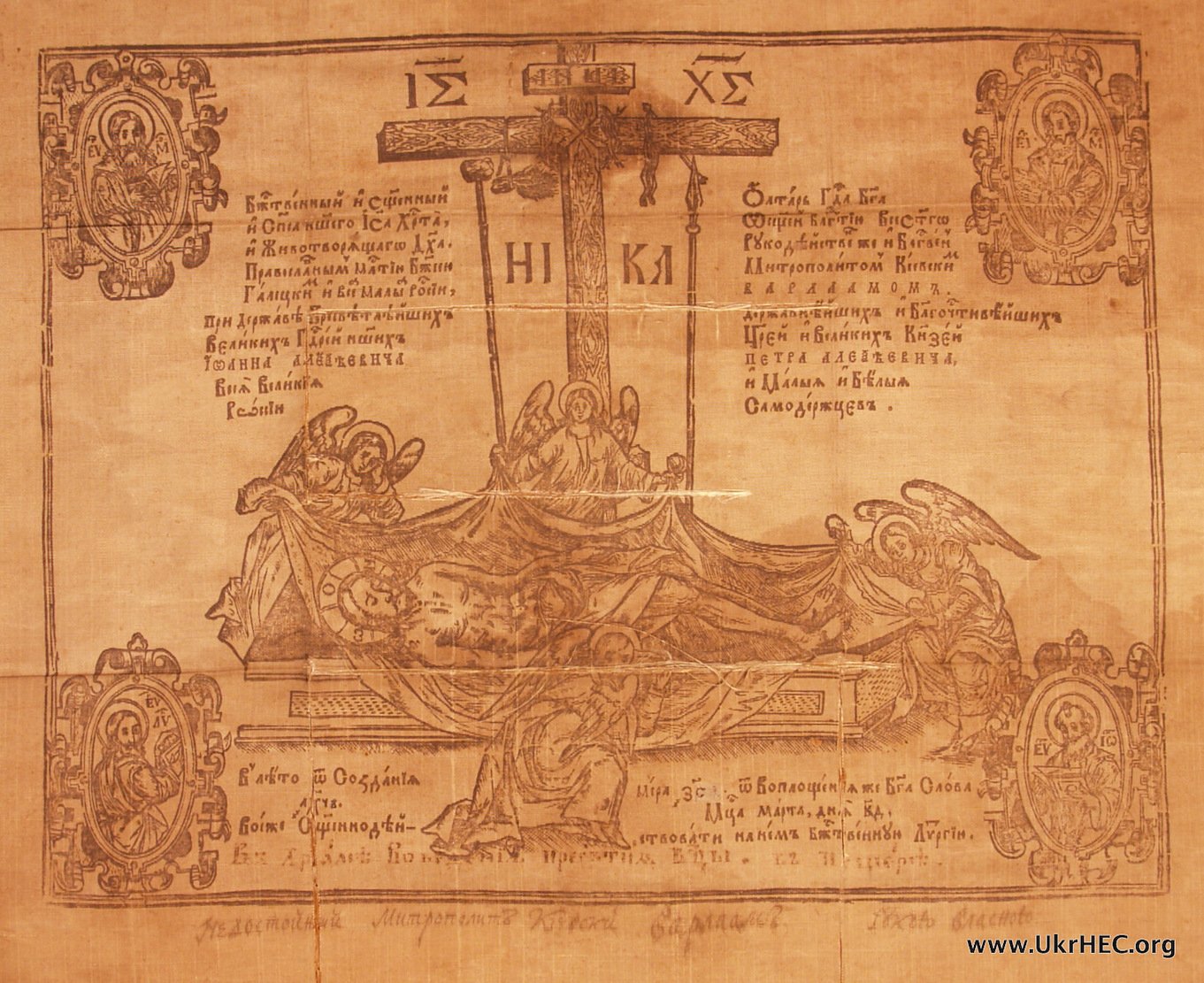

The museums of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra include numerous religious and liturgical objects, as wells as manuscripts and printed books dating from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, as well as objects associated with the local icon painting workshops and the printing house. The latter had a profound impact on the cultural development of the Lavra in the seventeenth century. The printing press and printmaking activities at the monastery began in 1616. The Ottoman pilgrim and clergyman Paul of Aleppo acknowledged the importance of the printing house at the Lavra in his mid-eighteenth-century writings. At the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, he wrote, “there is a known printing press that produces fine work for the whole country. All the Church books that are needed are printed here, in different formats, and finely ornamented. They also do large format prints, showing the curiosities of the land, the holy icons and works of art…” (Deluga and Zych, 1996, p. 10).

The monastery was well-known for its printed books, paper icons, and printed textiles. Woodcuts with religious iconographies were sold in large numbers to pilgrims, thus increasing the revenues of the monastery. Some of the earliest examples of such paper icons date to 1625–29 (Deluga and Zych, 1996, p. 11). One popular example was the icon showing the Pecherska Virgin with Saints Anthony and Theodosius, which recalled the thirteenth-century painted icon discussed above (Deluga and Zych, 1996, p. 15). About 3500 woodblocks, mostly from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, are kept in the archives of the monastery today.

Printed antimension, liturgical textile, Ukrainian History and Education Center Virtual Galleries, accessed August 1, 2022, https://www.ukrhec.org/gallery/items/show/74

Printed textiles were also produced at the monastery. Most popular were the antimensia – a liturgical textile used during the Eastern rituals. The most lavish examples were embroidered, but more affordable ones would be printed on silk or paper. The Book and Print History Museum at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra holds several examples of printed antimensia: one example, from 1621, shows Christ displaying a rotulus, and it is signed by archimandrite Hiob Borecki; another example, from 1620s, shows the entombment of Christ with angels and the four Evangelists in the corners, and it is signed by bishop Ezechiel J. Kurcewicz (Deluga and Zych, 1996, p. 16). These objects serve as historical records. They indicate that such antimensia were either commissioned or authenticated by local clerics whose names are preserved to this day.

Calendars were another popular printed artform created in the Lavra printing house. These included 12 sheets of paper, one for each month of the year, showing the saints celebrated in each month. The earliest examples executed in the Lavra workshop date to 1629 (Deluga and Zych, 1996, p. 17). Local artists also produced plans of the monastery for publication, as well as guides for specific holy places to aid pilgrims and the faithful in their spiritual journeys. The printing house at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra was so active, successful, and popular that it established connections throughout the Eastern Christian cultural spheres beginning in the seventeenth century.

A page from the calendar printed at the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, ca. 1628, and now in the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford (Bodleian Library Arch. B b.4).

The complex and diverse collections and archives of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, accumulated over centuries, demonstrate the intense activity, deep spirituality, and wide connections of the monastery within Kyiv, the wider Rus, and the even broader medieval and early modern cultural spheres. Although the monasticism of the Lavra was inspired mostly by Byzantine and Athonite monastic practices, it was also informed by Western monastic movements, especially the Cistercian order. It is known that the Cistercians had a leading presence across Europe, and even in areas of Eastern Europe, for much of the Middle Ages. The sources attest to these connections and the development of local textual and artistic forms in the Rus context at the crossroads of traditions.

Today, only a pale image of the former rich collections of icons, textiles, metalwork, woodwork, relics, books, prints, and more of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra survive. And these are further endangered by the current war in Ukraine. During World War II, German forces moved art around in local museums or removed it from the region altogether. Hundreds of icons and precious objects of the Lavra were placed in storage, others moved to nearby collections, and others removed to other countries. This shifting of the cultural heritage also resulted in works being stolen or illegally sold. A museum specialist by the name of Diedrich Roskamp recounted in a postwar testimony: “In a school near Kiev we found a lot of icons and other works of art which had been collected from the monastery of Lavra pending transfer to Germany.” (“Résumé of the Interrogation of Dr. Diedrich ROSKAMP,” fol. 204. Cited in Grimsted, 2013), p. 59).

The lack of documentation from the period poses serious problems to modern scholars who are trying to piece together the evidence and reconstruct the history and collections of the monastery. Eventually, some of the objects were returned to Kyiv, but only a small portion. Most were restituted to the former Soviet Union and ended up in Russian museums such as the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, while others entered international and private collections.

Display as part of the exhibition “The Revived Treasures of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra” – Twitter, 31 March 2016.

In the twenty-first century, and before the current war in Ukraine, the vast collections of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra were available for study and research. Scholarly and conservation efforts sought to unravel and revive the complex history of the monastery and its objects. Local exhibitions – like the 2016 exhibition “The Revived Treasures of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra” (from the collection of the National Kyiv-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Preserve) – aimed to showcase objects that had been recently restored. 120 works produced between the fifteenth and the twentieth centuries, and ranging from liturgical furnishing and icons to printed books and textiles, underscored the vibrancy of styles and iconographies, as well as the varied media and functions of the objects in the collection.

Throughout its long history, the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra accumulated, created, and used a wide array of religious objects in various media, demonstrating through its vast and growing collections the piety of patrons and of the local community, the creativity of artists and local workshops, as well as the deep spirituality of the site, its occupants, and its visitors. Future efforts could include the digitization of the collection in order to make it accessible to wider publics. Such a project could also bring together again, in a digital format, the objects from the monastic collection that had been dispersed throughout the world during the twentieth century and as a result of the current war.

At the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, the accumulation of valuable objects over time gradually enhanced the significance and holiness of the monastery within Rus, as well as within the broader medieval and modern spheres of Christianity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Rileigh K. Clarke for research assistance with this project.

Select Bibliography

Official website of the Kyiv Caves Lavra: https://lavra.ua/en/

Bilenky, Serhiy. Imperial Urbanism in the Borderlands: Kyiv, 1800 – 1905. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

Bosley, Richard David. “A History of the Veneration of SS. Theodosij and Antonij of the Kievan Caves Monastery, from the Eleventh to the Fifteenth Century.” PhD Dissertation, Yale University, 1980.

Cross, Samuel H., and Olgerd P Sherbowitz-Wetzor, trans. and ed. The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text. Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America, 1953.

Cybriwsky, Roman Adrian. Along Ukraine’s River: A Social and Environmental History of the Dnipro (Dnieper). Budapest: Central European University Press, 2018.

Deluga, Waldemar, and Iwona Zych. “Prints for a Monastery in Kiev.” Print Quarterly 13, no.1 (March 1996): 10–19.

Garcia de la Puente, Ines. “Gleb of Minsk’s Widow: Neglected Evidence on the Rule of a Woman in Rus’ian History?” Russian History 39, no. 3 (2012): 347–78.

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. “Art and Icons Lost in East Prussia: The Fate of German Seizures from Kyiv Museums.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 61, no. 1 (2013): 47–91.

Heppell, Muriel, trans. The Paterik of the Kievan Caves Monastery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Jusupović, Adrian. “Bookmen, Scribes, and Literates: Writing in Rus between 1000-1400.” Medieval World: Culture & Conflict 2 (2022): 24–27.

Lewin, Paulina, et al. Seventeenth-century Writings on the Kievan Caves Monastery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Lilienfeld, Fairy von. “The Spirituality of the Early Kievan Caves Monastery.” In Christianity and the Eastern Slavs, vol. 1, Slavic Cultures in the Middle Ages, 69–72. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993.

Prestel, David. “The Search for the Word: Echoes of the Apophthegma in the Kievan Caves Patericon.” The Russian Review 57, no. 4 (1998): 568–82.

Prestel, David. “The Kievan Caves Monastery: What Do Monks Have To Do With the World?.” Russian History 33, no. 2–4 (2006): 199–216.

Prestel, David. “Holy Folly: Explorations of Humility in the Kievan Caves Monastery.” Russian History 44, no. 2–3 (2017): 371–92.

Thomson, Francis. “Saint Anthony of Kiev – The Facts and the Fiction: The Legend of the Blessing of Athos upon Early Russian Monasticism.” Byzantino-Slavica 56 (1995): 637–68.

Walton, Kathryn. “The Strange Tale of Brother Isaac: Holy Fools and the Lives of Medieval Monks.” Medieval World: Culture & Conflict 2 (2022): 48–51.

Alice Isabella Sullivan, PhD is Assistant Professor of Medieval Art and Architecture and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at Tufts University. She is co-founder of North of Byzantium and editor of Medieval World: Culture & Conflict.