The Roquepertuse sanctuary

By Ian Armit

This view of the Roquepertuse sanctuary shows the walled terraces to the right, cut into the edge of limestone plateau. The buildings in the foreground also date to the Iron Age.

The Iron Age sanctuary of Roquepertuse lies near the village of Velaux, Bouches-du-Rhône, in southern France. Still clearly visible today, partly as the result of successive archaeological excavations, it comprises a rising series of walled terraces set into the gentle south-east slope of an otherwise sheer-sided plateau over-looking the valley of the River Arc (Armit 2012). The white limestone cliffs surrounding the plateau would have made this a prominent landmark, although the sanctuary itself was hidden from the valley.

Following the discovery of sculptural fragments during agricultural operations, the first archaeological investigations were conducted by Henri de Gérin-Ricard from 1919-27 (Gérin-Ricard 1927, 1929). Although this early work uncovered many of the well-known sculptures and carvings from the site, it was a renewed programme of scientific excavations led by Philippe Boissinot in the 1990s that unravelled the archaeological sequence as we now understand it (Boissinot 2004; Lescure 2004). Although the stratigraphy of Roquepertuse is immensely complicated (Boissinot has defined 14 successive ‘periods’ of occupation; 2004, 59), it is possible to compress these into three main phases: the early sanctuary; the monumental sanctuary; and the destruction and subsequent re-use of the site (Armit 2012, Chap 5).

The early sanctuary

The oldest objects found at Roquepertuse comprise a group of around 30 small stone stelae, mostly recovered from later buildings where they had been incorporated as building material (Lescure 2004, 46). These simple carved stones probably date to the Bronze Age or the earliest part of the Iron Age (cf Gantès 1990), and suggest a long history of ritual activity on the site. The most dramatic remnants of the early sanctuary, however, are a series of near-life-sized seated warrior figures, carved from local Coudoux limestone. Judging by the number of fragments, there may have been as many as ten such statues in the early sanctuary, but only two survive reasonably intact. Each wears a short tunic and a distinctive cuirass with a stiffened back-plate and square neck-guard, all of which were originally painted with bright geometric designs. These slim and sinuously carved figures, seated with their legs crossed in ‘buddhic’ fashion, seem to radiate peacefulness and calm (Benoît 1955, 42), although both their body armour and the sheathed swords carried at their waists demonstrate their martial nature. This warrior attire is typical of the fifth century BC (Arcelin and Rapin 2003, 206; Rapin 2004), and the same broad dating probably applies to a finely-carved stone Janus head that once formed part of a larger architectural construction.

This seated warrior figure is one of perhaps as many as ten that date to the fifth century BC.

All of these sculptural fragments were found in the ruins of the later, monumental sanctuary, so it is not clear how they were originally displayed. The crisp detail preserved on the soft limestone tells us that they must always have been protected from the elements, so they may have been housed in roofed structures or else in niches within the cliffs. Aside from the sculptural evidence itself, there are few archaeological indications of the early sanctuary. The earliest securely-dated structures comprise several oval, clay-walled buildings dating to the fifth century BC, and they are thus broadly contemporary with the warrior statues and Janus head. These structures appear to have been irregularly scattered around the base of the plateau, with no obvious order or planning. Yet even this relatively minimal evidence for settlement seems to vanish altogether in the fourth century BC (Boissinot 2003, 238), making it hard to judge the nature or layout of the early sanctuary.

This photograph shows one of the large ‘niches’ in the cliffs around the plateau.

The monumental sanctuary

Around 300 BC, the sanctuary was radically transformed. A substantial rampart, complete with two round towers, was built across the only access point to the plateau, creating a small defended enclosure within which lay the walled terraces which formed the ritual focus of the site. On these was created a monumental stone portico, formed of pillars and lintels, with carved niches which displayed severed human heads. The remains of some of these heads were found still embedded in their niches during the early excavations.

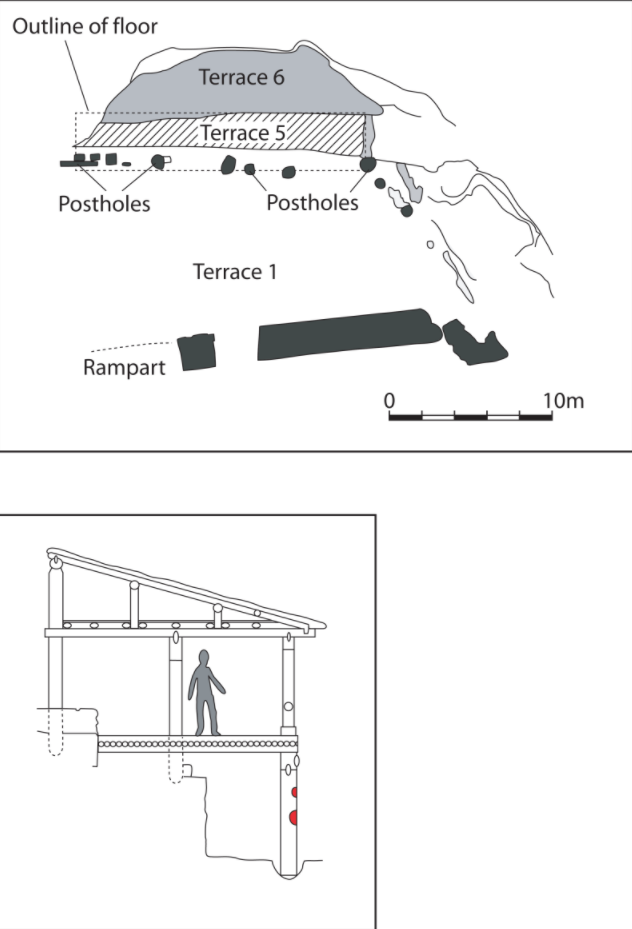

Simplified plan of the monumental sanctuary.

Roquepertuse is one of a number of Iron Age sanctuaries in this region where human heads were displayed in elaborate, sometimes monumental, surroundings (other notable examples include Entremont, on the outskirts of modern Aix-en-Provence, and Glanon, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence). There have been various theories as to whether these heads represent the remains of vanquished enemies or venerated ancestors. The former appears more likely based on the evidence for violence seen in the human remains from several sites (Armit 2012) but it is impossible to be sure. What is clear, is that the heads were in various states of repair when the portico was created, since each niche seems to have been individually shaped to receive a specific head, some of which were apparently complete and others represented by just a cranium or frontal bone. This suggests that the collection may have been curated over a long period rather than representing the fresh trophies from a single violent episode.

Although dominated by the dramatic head niches, the portico structure was also painted with a mix of animal motifs and geometric designs. The animals are mostly horses, snakes and ravens, although a sea-horse also appears, and a solitary human figure on one pillar is associated with a large disc (Coignard and Coignard 1991, 31) that may be a sun symbol. The importance of the horse is reinforced by burial of two horses close to the portico (Gérin-Ricard 1927, 33-4). Indeed, Patrice Arcelin has suggested that the horse was regarded as a psychopomp (Arcelin et al 1992, 218), or spirit guide, charged with leading the newly dead safely to the afterlife. Cross-culturally, psychopomps very often take animal forms and these recurrently include horses and birds of various kinds. The animals which would have been most commonly encountered in the daily lives of the people of the region (e.g. cattle, goats, sheep, pigs and dogs) are absent from the iconography.

This drawing shows the geometric and animal motifs that adorned one of the pillars forming the portico. The pillar is ‘opened out’ to show the decoration of both sides as well as the front. The shaded ovals are the niches, which originally contained human heads.

It seems that the (by now rather ancient) warrior statues were also displayed alongside this portico structure and a three-dimensional stone sculpture of a bird of prey, some 60cm high, was also reassembled from around 25 fragments recovered from the early excavations (Lescure 1990, 171 no. 6). By the early third century BC, therefore, the now monumental sanctuary housed a remarkable collection of art and objects, some newly created, and others at least two hundred years old.

Iconoclasm

After perhaps a couple of generations, the sanctuary underwent a further transformation. Although there is no obvious sign of burning or damage to buildings, it is clear from the numerous fragments of deliberately broken stone statues and pillars built into the walls and floors of the next generation of buildings, that a major episode of iconoclastic destruction had occurred (Boissinot 2004, 51). The monumental portico structure was cast down, and the statues broken up, in some cases into tiny fragments. Even the two near-complete warrior statues, discussed above, had to be painstakingly reassembled from numerous fragments. And it is surely significant, given the association of the sanctuary with trophy heads, that not a single head survives from any of the warrior statues.

Following this violent destruction, the number of buildings seems to have increased, although there is no evidence for any ongoing religious use for the site; it may by now have been a purely secular settlement. By around 200 BC, perhaps another two generations after the iconoclastic episode, the remaining buildings at Roquepertuse were violently destroyed and the site was never again occupied.

The monumental sanctuary. The top image shows a plan view of the main features recovered through archaeological excavation while the bottom image shows a possible reconstruction of the building in profile.

References

Arcelin, P., B. Dedet & M. Schwaller. 1992. Espaces public, espaces religieux protohistoriques en Gaule méridionale. Documents d’Archéologie Méridionale 15: 181-248.

Arcelin, P. & A. Rapin. 2003. L’iconographie anthropomorphe de l’Age du Fer en Gaule Méditeranée, pp. 183-220 in O. Büchsenschütz, A. Bulard, M.-B. Chardenoux, & N. Ginoux (eds.) Decors, Images et Signes de l’Age du Fer Européen. XXVI Colloque de l’Association Française pour l’Etude de l’Age du Fer, Paris et Saint-Denis, 2002. Tours FERACF.

Armit, I. 2012. Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benoît, F. 1955. L’Art Primitif Méditerranéen de la Vallée du Rhône. Gap: Ophrys.

Boissinot, P. 2003. Notice 7 : Velaux (Bouches-du-Rhône), pp. 238-41 in Arcelin, P, & Brunaux, J.-L. (eds.) Cultes et sanctuaires en France à l’âge du Fer. Gallia 60: 1-268.

Boissinot, P. 2004. Usage et circulation des éléments lapidaire de Roquepertuse. Documents Archéologie Méridionale 27: 49-62.

Boissinot, P. & Gantès, L.-F. 2000. La chronologie de Roquepertuse. Propositions préliminaires à l’issue des campagnes 1994-1999. Documents Archéologie Méridionale 27: 249-71.

Boissinot, P. & Lescure, B. 1998. Nouvelles recherches sur le ‘sanctuaire’ de Roquepertuse à Velaux (IIIe s.). Premier résultats. Documents Archéologie Méridionale 21: 84–9.

Coignard, R. & Coignard, O. 1991. L’assemble lapidaire de Roquepertuse : nouvelle approche. Documents Archéologie Méridionale 14: 27-42.

Gantès, L. F. 1990. Roquepertuse : le site protohistorique, pp. 162-4 in Musées de Marseille Voyage en Massalie : 100 Ans d’Archéologie en Gaule du Sud. Marseille: Edisud.

Gérin-Ricard, H. de 1927. Le Sanctuaire Préromain de Roquepertuse à Velaux (Bouches-du-Rhône). Son Trophée – Ses Peintures – Ses Sculptures. Étude sur l’Art Gaulois avant le Temps Classiques. Marseille: Société de Statistique, d’Histoire, et d’Archéologie de Marseille et de Provence.

Gérin-Ricard, H. de 1929. Le Sanctuaire Préromain de Roquepertuse (fouilles de 1927) : Étude sur l’Art Gaulois avant le Temps Classiques (Supplément). Marseille: Provincia.

Lescure, B. 1990. Roquepertuse : collection archeologique, pp. 165-71 in Musées de Marseille Voyage en Massalie : 100 Ans d’Archéologie en Gaule du Sud. Marseille: Edisud.

Lescure, B. 2004. La statuaire de Roquepertuse et ses nouveaux indices d’interprétation àl’issue des fouilles récentes. Documents Archéologie Méridionale 27: 49-62.

Rapin, A. 2003. De Roquepertuse à Entremont, la grande sculpture du Midi de la Gaule. Madrider Mittielungen 44: 223-46.

Acknowledgements

Parts of the text are adapted from Chapter 5 of the author’s Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Professor Ian Armit is Chair in Archaeology at the University of York. His research centres on the cultural archaeology of the European Later Bronze and Iron Ages, the role of conflict and violence in non-state societies, and the demographic and genetic prehistory of European populations. He has directed fieldwork projects in Scotland, France and Sicily and has also worked extensively in south-east Europe. His recent books include Headhunting and the Body in Iron Age Europe (2012) and Darkness Visible: the Sculptor’s Cave, Covesea from the Bronze Age to the Picts (2020), the latter co-written with Dr Lindsey Büster. He currently runs the ERC-funded COMMIOS Project.